Proxy ARP Sucks

Proxy ARP was often used in network designs 10–15 years ago, to enable NAT. It helped get around some specific challenges, but it was always an administrative hassle, and caused significant scaling issues. There’s very little reason to use it these days, but sadly it still lingers on, just waiting to catch out junior engineers.

Proxy ARP History

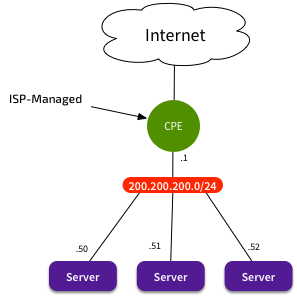

15+ years ago, Enterprises would have a small public IP allocation, delivered to them by their local ISP. The ISP would manage the CPE, and present an Ethernet connection to the Enterprise. That local network would be the public subnet - e.g. 200.200.200.0/24. You could plug in a switch, and directly connect your servers. Give them an address from 200.200.200.0/24, and set the default gateway to be the CPE. Done.

Legacy Connection - No NAT needed

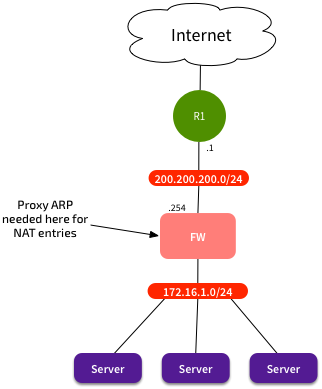

But hang on, what if we wanted to use a firewall? And what about NAT? That started coming into wide-spread use, and Enterprises liked the idea of being able to use a small public IP range for many internal systems. Now our network looks like this:

Proxy ARP now required

The problem now is that our servers have internal private IP addresses. The firewall and CPE are using IPs in the 200.200.200.0/24 range, but how can we NAT say 200.200.200.50 to our internal server at 172.16.10.10? We can configure the NAT policy on our firewall, but we still need a way to get the CPE to forward frames to the firewall, so it can translate them, and forward them on. The problem is that if the CPE needs to forward traffic to 200.200.200.50, it assumes that it’s a locally connected system, and so it sends out an ARP broadcast.

This is where proxy ARP comes in. We could configure proxy ARP on the firewall to say “In addition to your own interface IPs, if you see an ARP request for 200.200.200.50, then respond with your own MAC address.” The CPE would get an ARP response from the firewall, and forward the frames to the firewall’s MAC.

The firewall would see its MAC as the destination, recognise that it needed to process the frame, see that it was to an IP that it had a NAT policy for, apply the NAT policy, and forward the packet to the internal private IP.

That’s all good, and it got around our problem. From the ISP’s perspective, nothing changed - their CPE still had a local public subnet, but now the Enterprise could get that traffic forwarded to different parts of their internal network.

What’s Wrong With It Then?

There are three issues with this setup:

- It’s an administrative hassle. Configuring a NAT rule alone isn’t enough - you also need to make sure that the firewall has a proxy ARP entry configured. Some firewalls automatically added NAT entries, others required separate configuration. In the case of Check Point systems, this could be especially jarring, as the NAT rule would be configured within the Check Point software, but the proxy ARP configuration depended on whatever OS Check Point was running on. Many, many firewall change requests were made without checking that a proxy ARP entry existed, resulting in failed changes and re-work. In ITIL shops, this often meant waiting a week until the next change window.

- How do you scale? What happens when you’ve used all of your 200.200.200.0/24 allocation? Your ISP might assign you 200.200.237.0/24, but how do you use it? We ended up doing terribly ugly things like putting secondary addresses on the CPE and firewall. Secondary addresses are always a hack, and can result in unexpected behaviour.

- This approach wastes addresses, particularly as you scale. Each new allocation wastes the network & broadcast addresses, and the IPs assigned to the gateways. Those public IPs can’t be used for NAT.

What Should We Do Instead?

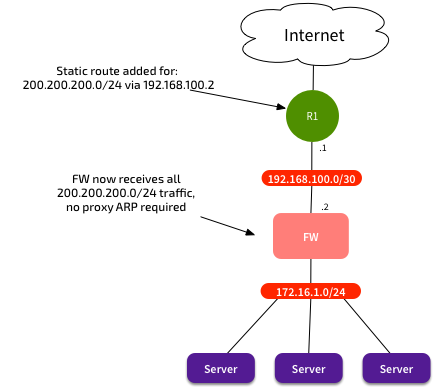

People started thinking that NAT somehow required the use of proxy ARP, forgetting the basics of Ethernet/IP/ARP operation. They forgot that all it was there for was so that the packets with a NAT IP destination would get forward to the firewall, so it could process them. The actual NAT policies on the firewall didn’t care about proxy ARP - they just needed to somehow receive the packets, so they could translate and forward them. People thought that a firewall could only NAT IPs that were on a locally connected network, but of course that’s not necessary.

Once we understand that, then the answer is simple: Just set up your routing so that the subnet you want to use for NAT is routed to the firewall. Could be done with static or dynamic routing:

This means that we can now use ALL of the NAT range for NAT - no wasted subnet/broadcast IPs, or need to use any for the gateways themselves. Now when we need to scale the solution, we just route another subnet towards the firewall. No manual proxy ARP configuration required for new NAT entries either - just define the firewall policy, and be done with it. Simpler configurations, simpler troubleshooting, better networking.

There was one wrinkle: If you didn’t control the routing on the CPE, you were reliant on your ISP making the change. In the early 2000s, some of them wouldn’t do it, and you were stuck. By the mid-2000s, most ISPs would do it. You would be very unlucky to find an ISP today that wouldn’t make this sort of change.

Why Is it Still Around Then?

Old habits die hard. Most of us have gotten over it, but there’s still a lot of people who think that NAT somehow requires proxy ARP. It’s remarkable how often it still pops up, given the pain it causes, and that network engineers wouldn’t dream of running a network with hundreds of host routes…yet proxy ARP isn’t much different.

Proxy ARP was always a kludge. Don’t allow it as part of your designs. Rip it out where you find it.